TRICKHOUSE | DIPTYCHS

February 2013

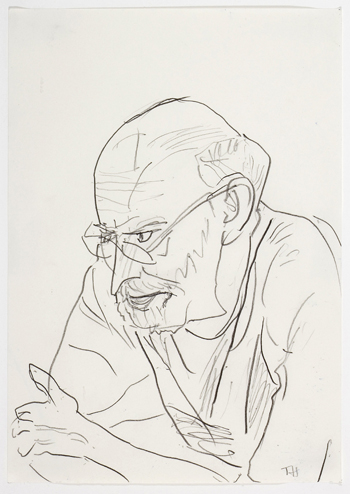

IN CONVERSATION WITH TIMOTHY HYMAN

BY NOAH SATERSTROM

I first met Tim Hyman in Glasgow in 1999 when he came up to give a lecture on Pierre Bonnard at the Glasgow School of Art while I was on the MFA program. I approached him after his talk and he graciously visited my studio that day and gave me an inspiring two-hour lambasting. We have kept in touch ever since, and the following edited conversation was conducted over email from 2010 to 2012.

Noah Saterstrom: The books around me this week: Ken Kiff, Steven Campbell, your Sienese book, Jeffery Camp, Hogarth, Bhupen Khakhar, Daniel Santoro, and Goya’s Los Caprichos. Some of these we discussed when you first grilled me about the figures in my paintings years ago in Glasgow. Can you give a little background, how did you come to figurative painting? What was going on in painting when you were coming up?

Timothy Hyman: If I do ever manage to collect together the essays I’ve written on 20th century painting, one working title might be: Figuration After Abstraction. I arrived at The Slade in 1963, aged 17, at the highest tide of New York’s Imperium. Barnett Newman was being photographed in front of Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue, Rothko and Pollock were already canonised, Stella was waiting in the wings. Warhol was also a scary presence. I had already ingested a huge dose of 14th and 15th century Italian painting, which afforded me a kind of protection.

Nevertheless, by 1964 the prevailing aesthetic climate, which I’d characterize as a kind of authoritarian emptiness – a cult of THE VOID as the only truth – had got to me and pitched me into an induced identity crisis, from which, like many others of my generation, I feel I have even now barely recovered.

NS: There were a lot of rules at that point for painters, and figures were completely unacceptable, right?

TH: I knew very little of the civil war between abstract and figurative painters that had convulsed the early 1950’s in Britain; abstraction had emerged so overwhelmingly victorious as to make all representational art appear an anomaly – a soft option, a lost cause, a “retrograde” step. And I had so internalized the metaphysic of abstraction – the more-or-less mystical aspiration towards a transcendent BEYOND – that I could not descend into the banality of the everyday, of the “merely” descriptive… Of course, I’m simplifying a situation that was really much more contested.

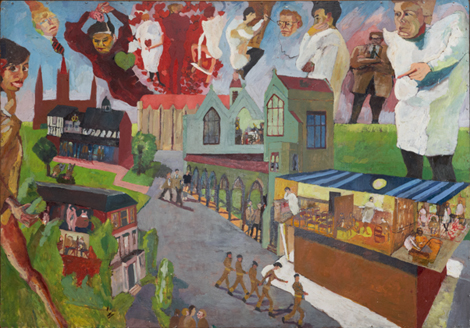

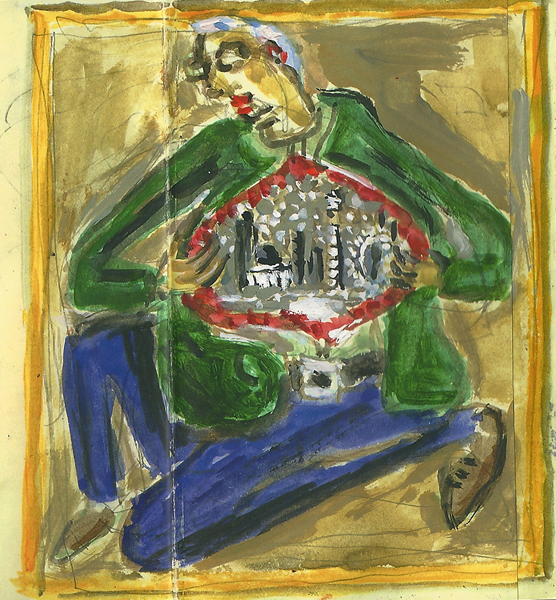

For example, The Slade hosted two home-grown art-sects: The Euston Road School, and The Bombergians. Both committed to a Modernist Figuration, but of a kind that eschewed the imaginative, the Narrative or History Painting, to emphasize “REPRESENTATION-AS-SUCH.” In a way, I came to find their brand of Figuration even more restrictive than the Abstract Sublime, and with an even more obtrusive overtone of Moral Superiority. I became very confused, and to some extent paralyzed. Yet by my final year at art school, in 1966-7, when most of my fellow students seemed to have evolved to hard-edge stripes, I had regressed to the “Gory Expressionism” of a picture I’ve just dug out of my store – and still like – The Party. It is a real twenty-year old virgin’s cry for help!

So one way of understanding the decade that followed – roughly from 1968 to 78, after which I began to exhibit “seriously,” though I had been painting almost every day throughout – might be that I needed to free myself from the burden of Thou-Shalt-Nots; needed, more specifically, to construct an alternative 20th century canon, which would help legitimize my own aesthetic transgressions. I had started out with a slate wiped clean – The Void as Tabula Rasa, as registering the impossibility of language.

Imagine my excitement as I uncovered a whole (still, at that time largely buried ) culture of 1920’s and 30’s Figuration. Late Leger, late Bonnard, Beckmann, early Balthus; near-unmentionables such as Stanley Spencer or Edward Burra or the first twenty great years of Chagall; wondrous forerunners such as Ensor; lesser but still rewarding figures like Carrà or Hopper or Jack Yeats; Dix and the Neue Sachlichkeit; an amazing one-off like Charlotte Salomon… and even in postwar Britain, I found myself linked to fellow re-excavators of my own generation, as well as to Kitaj, and the (then sympathetically struggling, half-abstracted) Hodgkin, and the defeated Left – De Francia, Herman.

NS: One thread that seems to link most of these influences is neglect by the canon, at least at the time you were discovering them.

The “centers of ambition” have a program that is meant to be followed, and the collective ego in charge of deciding who is relevant and who is not really do a number on those who step outside the program. The worst fate the establishment can inflict is neglect… to write an artist off. But then it’s as if the neglected work then gets pitched into the reeds at the edge of town, waiting to be found later by someone seeking an alternative.

Many of your early influences are so extremely clumsy or awkward as to become exotic. The “grotesque” came into the sphere of influence for the handful of young figurative painters at the time – via Ensor? Who of your contemporaries were you drawn to?

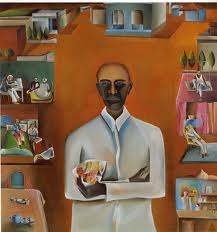

TH: My own metaphysic may have drawn me most to contemporaries of an “inward ” persuasion – Ken Kiff, Andrzej Jackowski – but my subject matter started to diverge; the “everyday” became my special territory – which is when I converged with Bhupen Khakhar and the Baroda school… None of the artists I’ve named are “straight” painters in any readymade academic tradition.

In most cases, they came close to abstraction at some point, and understood the threadbare-ness of much 19th century pictorial language. To build any authentic reinvention of the world, one would have to begin all over again, and one’s language was inevitably tinged with Primitivism. Guston and Golub, Alice Neel and late Marsden Hartley – they’re the Americans I’ve felt closest to – along with Henry Darger! All, in their various ways, might be described as “Rebuilding on a Destroyed Site” …

* * *

TH: Three days ago a dear American friend, Richard Maxwell – he taught Comparative Literature at Yale – died after a long struggle with a brain tumour. I dedicated my book of drawings to him in May; I felt he had a deep understanding of what I was all about, he’d bought two pictures, and 3 years ago gave me an interesting role in a Yale conference on THE PANORAMA. His own writing was often focused on the City-panorama – in Dickens, in the 19th century Mystery genre, etc.

We first met about 18 years ago as devotees of an extraordinary British writer of Panoramic Romances, John Cowper Powys. I’m bringing this in, because Powys probably had more influence on my art (and life) than any of the painters listed above. I read A Glastonbury Romance in 1963, and Weymouth Sandsin 1966 (they were written in the1930’s in Upstate New York, when Powys was already in his 60’s; he’d met Pound, was a witness at the trial of Joyce’s Ulysses, was close to Dreiser, but obstinately, KNOWING THE SCORE, continued to write these wayward huge fictions).

For Powys functioned as a sort of proto Post-modern aesthetic, which I think rescued me from mainstream conformism. But I also loved the man (born 1872, so I never met him), his anarchist creed, his creation of a world that challenges all Hierarchy, his walks, and above all his sense of the minutiae of the Everyday being inseparable from the Visionary. I joined the Powys society in 1970, attended the first ever Powys Conference at Cambridge in 1972, and most years ever since have spent 3 days in Summer, accumulating several of my closest friends thereby- too many now dead. This August, in Glastonbury, I’m very reluctantly taking over as Chairman.

For what it is worth the English near-contemporary I felt closest to was Ken Kiff, also a keen reader of Powys.

NS: A variation of your phrase “Everyday being inseparable from the Visionary” appears in your book on Bonnard, right? Something like his “little epiphanies.”

You mentioned that Powys has affected your life as well as your painting. The self-determination to be a “freelance” scholar, is that one of the ways that he has influenced you? Powys gave freelance lectures instead of following a prescribed academic path, like letting out a lot of slack in a kite string… better to be chaotic and full of life then rigid and emptied of it?

I mean, you are a painter, teacher, writer, curator, you lecture and teach at the big institutions, but unless I’m mistaken you’re not employed anywhere. What have you to say for yourself? Do you fear your boat will capsize at any time, or do you enjoy the pirate life? Or perhaps you don’t make these distinctions between inside and outside the institutional/academic safe zones.

TH: As you realize, I’ve never had a salaried job, and will get no pension. But yes, I do mostly “enjoy the pirate life” as you put it. I grew up in a family that believed it was securely rich, though cracks were already appearing before I was ten, and by the time our parents were dying in the late 1990’s they were financially dependant on their children, and especially on my twin who was struggling with cancer (d. 1999) and me (Judith already diagnosed with Parkinsons); the other two siblings shipwrecked. So money worry has often surfaced – for most of the past 15 years, only now lifting… perhaps not so much on my own account. When I first married Judith in 1982 it was she who helped me with her editorial salary – so it feels ok that I now have more “responsibility”…

* * *

NS: To move the conversation to your work… I’ve been spending time with you Fifty Drawings book.

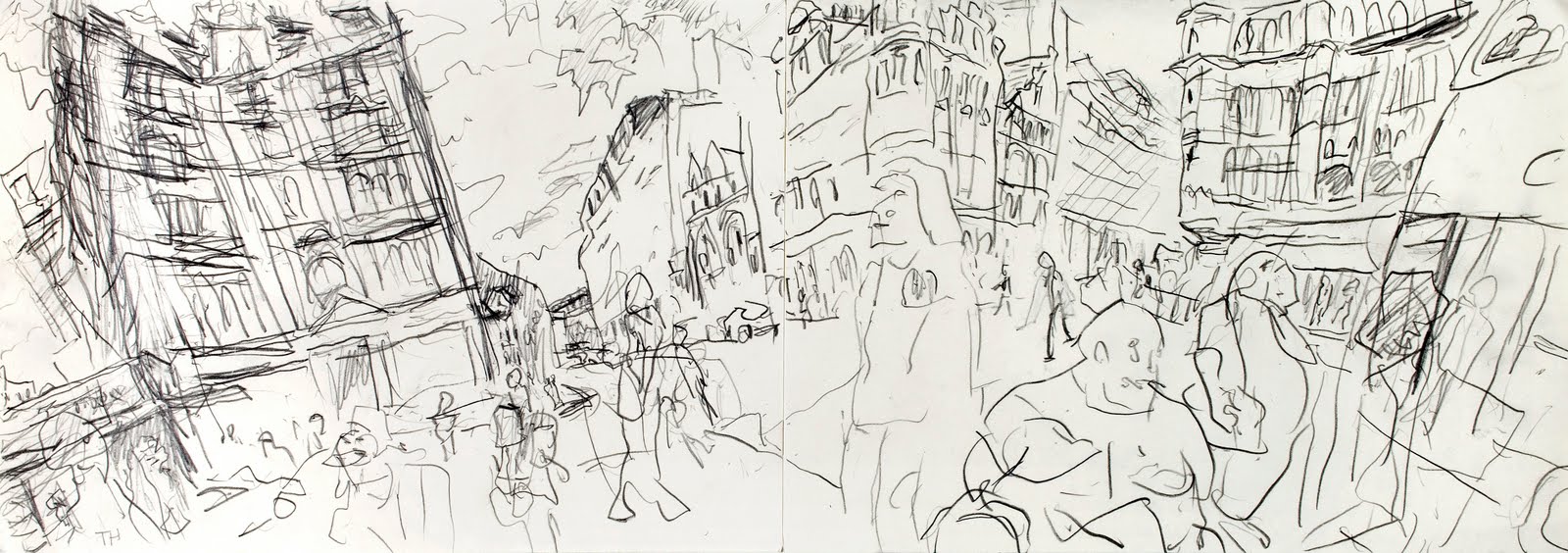

In your drawings, your lines rarely close shapes, forms stay open, and nothing gets fixed to a horizon or subject to gravity or physics. I am reminded of my kitchen cabinet that keeps swinging open on its own, it won’t stay closed. Your lines have a similar “uncooperative” quality, chattering and incomplete. But I know you to be physically and intellectually fastidious: the collarless shirts, the exacting fringe, the complete and cogent and directed thoughts, articulate and cosmopolitan… but your paintings, drawings and the many postcards I’ve received from you are unhinged, nearly illegible at times, vulnerable, excitable. When we started emailing, I was delighted to see that these unhinged qualities emerge even in your typing style (which I have reluctantly “cleaned up” for the sake of this dialogue) … irregular spacing, sudden and sometimes unwarranted ALL CAPS, erratic punctuation, and so on.

Not trying to make you uncomfortable by pointing out your appearance or communication style, and of course it’s only my perception, but your paintings are so often “first-person singular” that I have trouble separating how you move through your paintings and what your paintings are like, from how you move through the world. In this way your work is very different from Ken Kiff, for instance. I am attracted to the uncooperativeness of his images, and his Sequence is so loosely affixed as to be disorienting.

TH: I very much like your use of the inanimate – the kitchen cabinet unhinged – to embody psychological identity; perhaps there’s a potential strategy for your painting, for mine, in such transpositions and stand-ins?

Unhinged is spot-on. Judith sees it as redemptive, in the sense that it prevents my making out as establishment smoothie or socialite or committee-person, etc; I’ve come to realize that I don’t altogether “Inspire Confidence”… In some ways this ‘unhinged’ is a hangover from my very distressed adolescence; at boarding school, or in family or London Gang, I really could not discover a comfortable way of being-in-the-world, though I had friends always, heard confessions… and now that I am in the World, something of this aura of distress still hangs about me, disconcerting… Mad Monk, Spoiled Priest, Lost Soul.

I really was blasted by the full force of The Void and the imprint is indelible. But not separable from the awkward societal roles – Misfit/Zany/Fool/Creep – were the physical facts as a six or seven year old: couldn’t walk straight, left/right confusions, squint, all adding up to a hopeless case in all physical activities. ‘Oh Hyman, you are SPASTIC’ was a cry I often heard in my teens on the purgatorial games field; would it have helped to substitute ‘Dyspraxic ‘ – which would probably be the diagnosis now? This discomfort with the Body was exacerbated by my being a twin, dividing the world between us; Tony was Body, I was Head; Dead from the Neck Downwards… My sense of Self was gravely undermined. At twenty I felt it could have been said of me, ‘He looks as if he hasn’t been lived in for years.’

NS: Good grief! But in your work, because of your constant presence (meaning your actual likeness), there is nearly always a protagonist/narrator to keep things from fluttering away. I think of you, in your paintings, as being three things as once: the seeing-eye (which is also my seeing eye), the Virgil figure or tour guide (usually for London), and also the subject of my examination – all at once.

And I also do not separate your paintings from your scholarly writing and your personal life, so that when I see Around Bhupen, he has now become a character in the epic, and I Walk Down Grey Street loops me into Martini and Lorenzetti’s passages into the orifices of cities.

You place your self so firmly in your work as hero/fool. And all the conflicting information: utopian, inelegant, cosmopolitan, uncouth, dandy, palsied, grotesque intellectual, interloper… not forcing you into a box, just rattling off a few words that return to me looking at your work, noting their contradictions. The shape-shifting.

Do you remember the first time it occurred to you to enter yourself into your work directly?

TH: While a student at The Slade, I did identify two artists creating ‘self- imagery’: Jeffery Camp, who you mentioned earlier, and Anthony Green, who is more thoroughly anecdotal/autobiographical, but remarkable in his totality of life-project. Both very inventive in format (much more so than me ). I cold-shouldered Anthony, but came to respect his intelligence later on, and we are now old comrades… he bought a drawing from my last show. An amusing book is A Green Part of the World, he’s now in his late 70’s.

This interest in ‘self-imagery’ is borne out by the double picture I made in my first year at The Slade at seventeen/eighteen (… 1964, “Me and My Friends”; “Charterhouse and London”), before the confusions and imperatives of Modernism got to me. I dug them out for the studio move in August and had them photographed. They were not the first time I ‘d already appeared in my own imagery.

NS: I like those old paintings, shockingly consistent with what you are doing now. I can see why painting would suit your constitution. The brain is activated by painting and given a lot of space to roam, without clearly defined rights and wrongs, good for curious and restless minds. It is a physical activity, painting, but one in which failure, missteps and spasms are not just acceptable, but appreciated. Unlike sports. I love how being Painters allows us to professionally court indecision and faltering. Not so if we were say Lawyers, or Anaesthesiologists.

* * *

NS: You have written and painted about Bhupen Khakhar with such devotion, even a kind of starry-eyed admiration. Was there a romantic connection between you? Or did you think of him as a muse? I know that Judith has also showed up as a muse-like figure. The unhinged-ness we talked spoke about earlier, makes me wonder what part sexuality, on a broader level (the impulse to unhinge being such a part, if not the main element, of sexuality) plays in painting for you? Do you think of it in these terms?

TH: No, I never had even a flicker of sexual interest in Bhupen, but we did in the 70’s mutually confess a degree of sexual confusion, uncertainty… his own passion was for ancient old men – a gerontophile. My fantasies were, by contrast, and more conventionally – Angelic, though fortunately I never did molest any of those 12-year-old magic Ariels I was so touched by. In the little book, I try to recreate — under the comic persona supplied by Bhupen – something of that smutty yearning, perhaps for a childhood I never did complete! In reality, many of my wounds were healed after 1981 by Judith. But I do still cherish the Seraphic as a visionary dimension!

* * *

NS: You’ve mentioned a few times about Judith “healing wounds”. And we’ve been talking about sexuality and physicality, social rejection and fractured self-perception. How does painting figure into these issues for you? Is painting healing?

TH: Yes, painting can definitely heal – both artist and spectator – but it is also a re-opening of wounds – hence our daily reluctance to start work! In my own case, as I began to be exhibited more widely, of course I came to feel a less fragile sense of identity. But The Void still has to be faced every day, and one’s confusion, as well as insignificance, acknowledged anew.

NS: When I was in the UK for grad school in the late 90’s, I got the sense that my language was too warm and mystical for the art climate at that time. And now I find myself, by design, surrounded by poets and fiction writers. Writers seem to have; I’m generalizing now, an easier relationship with the Emotional, Confessional, Mythic, Personal content than painters do… placing themselves as the fractured narrators at the center of their work.

TH: My best intellectual dialogue/polarisation over the past 30 years has been with a writer/critic, Gabriel Josipovici (at 70, he’s recently become a bit of a celebrity here for his latest book of criticism, Whatever Happened to Modernism -Yale). Early in our friendship he defined our mutual antagonism – that he was a DRY ROMANTIC – Kafka, Beckett – and I, a WET ROMANTIC – Blake, Powys… yet I’ve helped ‘educate’ him to see the value of, say, Bonnard, or pre-1925 Chagall, or even Beckmann; while I owe much of my literary awareness to him – Thomas Bernhard, Perec… where we meet is above all in medieval art and literature. (Gabriel is one of the dedicatees of my Siena book).

But I must still hold to my own unspare, flabby, uncool, complicated, thick-with-atmosphere, all-over-the-place aesthetic and life-path! We can’t please them all! And let’s not forget, we must hope to find our eventual audience not among our artist-contemporaries, but in the much less narrowly-bounded cultural realms of the future…

NS: That’s a great distinction Gabriel makes between Wet and Dry Romantics, helpful to give these things a tactile nature.

Dry: spare, taut, simple, cool and directed.

Wet: Excessive, emotional, warm, complicated and sprawling.

And at both poles of this male/female (?) spectrum – if it can be described in those universal terms, yes might as well give them gender as well – is the possibility of dreaming? And where on the spectrum is Sentimentality?

TH: The acceptable parameters of Sentiment – like “Illustration” – have shifted greatly in the course of my lifetime. Joyce’s definition of sentimentality – UNEARNED EMOTION – may be helpful.

But many of the suppressions peddled by Greenberg et al now appear merely ungenerous, mean-spirited. “Its only the fool who plays it cool”… and I would always prefer to risk the opposite folly!

Some kind of astringency and formal tension ARE present in most of the art I love best, and some of your drawings may topple into CUTE – but don’t be discouraged. Artists who have worked in dreamlike sequences have often been extremely uneven: Blake, Redon, Kubin, Tagore, Jack Yeats, Kiff… Goya perhaps the exception…

NS: The point is well taken in regards to my work, I see the tendency to pad my work with a layer or two of stuffing, I’m content to acknowledge it and create alternatives, with increasing willingness to fail maybe.

I feel iffy about working in ways that could be described as “dreamlike sequences.” I agree that painters who sojourn in dreamland for imagery can go flakey. It’s sticky,

leaving the visible/verifiable world (which includes formal abstraction) for the inner, subterranean, aquatic sources of imagery.

Generating those dream forms and narratives, or submitting to them, it’s quicksand, so easily sinking into pudgy self-indulgent contrivances; worse, mere hallucinations. A survey of Surrealist painters shows lots of awkwardness with dreams. Arbitrary, cliché and psychedelic, that’s the Surrealist legacy that’s been handed down to so many “arts districts” painters studios. But the Dream is the territory that feels least safe to me right now, so… onward… keeping someone nearby to throw a rope if things get dire!

What do you feel about playing with language, forms… thinking of Perec’s Oulipo and that mode of approaching the unknown through systems and permutations… maybe in painting, Terry Winters, Jennifer Bartlett, Brice Marden… not cold work, but guided by external rules? Interest you at all? Black Mountain College experiments, John Cage for music, Merce Cunningham for dance, Sol Le Witt… now in standard use for contemporary poetics… using systems and external constraints to weasel your way into the unknown? Too monastic for you? Too dry?

TH: My New York friend Trevor Winkfield paints in Harry Matthews’ empty house, translates Roussel, is close to Ashbery… and I did hear several impressively charming Cage discourses at the AA when I was at the Slade. But none of this is quite my cup of tea! Too ‘thin’ ? Too ‘elegant’? As you’ve already understood, my art is in some ways very OBVIOUS in its intellectual underpinning. Don’t hold back from telling me whatever is problematic in this ‘Simplicity ‘ – its high time someone did!

NS: What you do is very old-school in a way, pre-conceptual, aligned with the ‘peasant’. I assume you’ve gotten a lot of criticism for that over the years, am I wrong; the British arts being so much informed by the bourgeoisie, historically? Strangely, I don’t find your paintings to be particularly intellectual, which is surprising to me, because I know that you are. One time you said to me that it’s best if you take in Redon’s paintings in tandem with his writings in “A Soi-Meme” – I might say the same about your painting, encountered alongside your writing on painting (like on the side of pill bottle: best taken with food… your writing would help with the absorption of the paintings into the bloodstream…).

Your words are crisp and clear, but your paintings can be mumbly and I wish you’d just come out with it, but then I get to something like the Emblems paintings of the figure (self?) who has zipped himself open to reveal a snowy London. Perfect. That image and others are murky to such great effect.

* * *

NS: I have been reading, at your suggestion, Redon’s journals. I like his assessments, at one point he criticizes Rubens for not having ‘experienced the grief of suffering’ which is the reason he gives for why Rubens is not great. This suggests that innocence doesn’t run deep enough to make good art. Innocence in painting? Grief, remorse, love, regret in painting? Do you have a preference or opinion about it? Early on in our talk you said you thought of me as an ‘Innocent’, but I didn’t take it as a criticism, should I have? Or maybe I did, I can’t remember.

TH: Rilke wrote often about the need artists have to re-enter the space of their own childhood experience – and of course Balthus’ best work will be all about that child-continuity. I think I am so moved by “Angels” – by rare, radiant, perfected pre-pubertal boy-children – because my own experience of childhood was so imperfect, dark, contorted! It is as though, through the Magic Child, one can re-enter, and have a second chance. Hence “Through the Looking Glass” and the note of Strangeness sounded in all the greatest Children’s Literature. And it is there too in the Infantilism of so much of the best 20th century art – including several of those recent drawings of yours!

* * *

TH: To press you a little on the “Very old-school” issue: how disabling do you think that is? Is it a sense of deja-vu , it’s all been done before, and does that (chiefly) make TH not a serious contender – or are there other factors? Is it irremediable? Is there any advice you would give to me as tutee – how to give it more street-cred?

As to ‘intellectual” – well, I’m an auto-didact , went to art school at barely 17, never fully came to terms with formal philosophy (can’t do logic) let alone Derrida and Theory… Deep down I’m a simple soul, not an intellectual… When I was 35, someone observed: You write like an old man, but you paint like an adolescent.

NS: Of course I don’t know anything about being a serious contender! Regarding the deja-vu, the idea that it’s been done before… I can never find anything to hold onto with that claim. Waking up has been done before, so has marriage, and so has divorce, pissing, gardening, eating lasagna, but there’s a freshness to all those things.

And of course it’s exciting when something happens that truly hasn’t been done before, but those are rare, and I’m not convinced that should be the goal, ever, for artists. If it’s an accidental outcome, great.

If you are working with timeless human dimensions – like self, myth, narrative, city, longing, memory – you are going along well-traveled roads. All the discovery is nuanced, not flamboyant. It may come down to taste, but the artists I tend to discredit are those that are stuck in a traditional/formal cul-de-sac. That is not the kind of ‘old-school’ I mean with your work. Maybe a better way to say it is your work is ‘timeless’, and maybe that is a handicap to being ‘current’ — maybe even irremediable — by a floppy trendy definition of ‘current’.

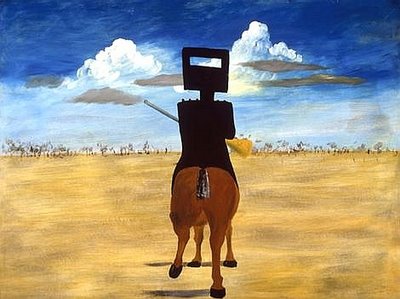

But other timeless qualities, which are never out of date (also aligned with the Peasant, rather than the Bourgeoisie): Silliness and Playfulness. You mentioned Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly paintings at some point, Silliness in painting? Any thoughts?

TH: A propos of SILLINESS, here is a favourite Spencer of 1937, being auctioned by Sotheby’s Wednesday night – Sunflower and Dog Worship.

He followed his fantasy to the limit: the idea of ordinary 1930s middle-class English flower-arrangers and dog-lovers taking it all A STEP FURTHER. They have been overcome by the impulse of an all-consuming cosmic love! At this point, silly and profound become hyphenated. It is one panel from Stanley Spencer’s huge cycle of imagery designed for his “Church of Me”, where the life of his local village will be transformed in the Last Days. It is, you might say, unashamedly “illustrational” – and very like a children’s book illustration in its ragdoll stylizations. Very understandably in the 1960s the then director of the Tate refused it as a gift; at Sotheby’s it fetched, I think, around five million pounds.

For me Nolan’s Ned Kelly series aren’t quite in the same category; their child-language is more calculated and they don’t seem “silly” at all. But the child-idiom does allow him to bring off a marvellous narrative, when seen all together.

* * *

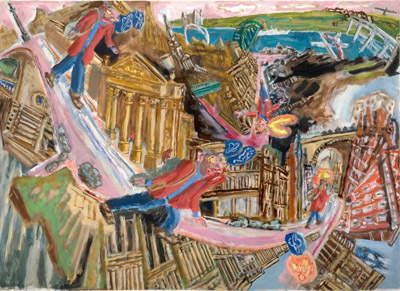

NS: Speaking of the hyphenated Silly-profound, what would you say about the distortion of space in your paintings?

TH: Issues of curved space or, as Paula Rego accused both me and Bonnard, WONKY space. An old friend (Charles Lock, Professor of English at Copenhagen) has sent me an article on the subject of “reverse perspective”, mainly in reference to Russian Icon painting. As he puts it, “where space appears to be poorly represented or mismanaged in art, this may not be due to an absence of perspective: such represented spaces may have their own logic, their own principles of organisation.”

I wouldn’t in fact claim any such systematic logic. But Charles goes on to suggest that whereas perspective may be an attempt to normalize the world, to make it orthodox, alternative modes of space may embody an encounter with “The Unfathomable.” That certainly rings a bell with me; I think I first skewed and tilted and stretched space because I wanted to de-familiarise reality. Orthodox perspective embodies a kind of enlightenment, an aesthetic distancing, detachment, restraint – the Apollonian. I wanted to find a spatial language that would allow multiple and contradictory viewpoints (Charles writes of “Redemptive Discontinuity”) and that language needed to have something of the Dionysian.

NS: An “encounter with ‘The Unfathomable’” – is that a divine presence that distorts?

The curvature of space of some of those great Sienese paintings, the elliptical domain of humans under the eyes of God, the expanse. The Panoramic, as I understand it, has a theological (Cosmic?) aspect, the all-seeing eye in the sky, the Panopticon.

Can we talk about painting before the Renaissance as pre-perspective and Cubism the beginning of a post-perspective painting?

TH: Obviously one interpretation of early Cubism would emphasize its disruptive potential and I think most contemporary painters do feel themselves “post-perspectival”.

But my own case, as I explained to Charles, is made a little different by a sense of comic absurdity, surely very far from the spiritual timbre of Russian Icon aesthetics? No, he rejoined: didn’t I realize that comedy and absurdity were very much part of the Russian Orthodox tradition, hence Bakhtin and Carnivalesque, hence St. Basil’s Cathedral at the heart of Moscow, dedicated not to the Greek Church Father, but to the obscure Russian Holy Fool.

NS: So following the rules of perspective implies a trust in logic (and a rational deity) and to distort perspective is to embrace absurdity (a disruptive deity?), whether we are talking about 14th c. painting, or a 20th century painting?

TH: When Nabokov writes about Gogol he observes that only one letter separates the Comic from the Cosmic. And cosmology does enter into any language that emphasizes curvatures; and perhaps the curvatures also imply cyclic experience. But of course there is a cost. As Gombrich and others make clear, the presence of vertical and horizontal stability is fundamental to the way human beings negotiate the world and to lose that grid-like structure is to lose one’s footing – perhaps one’s dignity. One frequent response I’ve also encountered to my spatial discontinuities is that of Apocalypse – of the ground shaking under our feet. I’d be happy with that.

Noah Saterstrom

Raised in Mississippi and educated at the Glasgow School of Art, Noah Saterstrom is a visual artist, writer, and Head Curator of Trickhouse.org. In addition to painting and drawing, he has made video works (Empty Houses, 2008), written essays (Amateur Art, Denver Quarterly, 2007) and an animation with writer Kate Bernheimer (Wastrels Find a Home). Recent exhibitions include a text/image collaboration with poet Anne Waldman entitledSoldiering (University of Arizona Poetry Center, Blaze Vox Books), 5 Text/Image Collaborations (Warren Wilson College, Asheville, NC), Bunny Magic: 100 Works on Paper (Yardmeter Editions, Brooklyn, NY), Now We’ll Decide Who Comes from Where (Carol Robinson Gallery, New Orleans, LA) and Memory[Memory](Lodginghouse Mission Homeless Shelter, Glasgow, Scotland). He maintains Noah’s Work-a-Day Page where he posts drawings and paintings on a daily basis. www.noahsaterstrom.com